The Meaning of Melancholy

An Interview with Hans Maes

Melencolia I by Albrecht Dürer, 1514

Dr Hans Maes is senior lecturer in history and philosophy of art at the University of Kent, United Kingdom. He has authored and edited a number of books including: Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, Before Midnight: A Philosophical Exploration (Routledge 2021); Portraits and Philosophy (Routledge, 2020); Conversations on Art and Aesthetics (Oxford University Press, 2017); Pornographic Art and The Aesthetics of Pornography (Palgrave MacMillan, 2013); and Art & Pornography (Oxford University Press, 2012).

In the interview below, we discuss the history and meaning of melancholy, a rich but often under-appreciated concept. You can read Maes’ full paper, Aesthetic Melancholy (2023), at Contemporary Aesthetics.

On the Arts: How do you define melancholy, exactly?

Hans Maes: Melancholy, as I understand it, arises when we grasp a profound but painful truth about the world, such as the transience of all things, the judgmental nature of human beings, or the indifference of the universe. These existential insights can make us feel anxious, hopeless, or lonely, but they can also make us appreciate more deeply the things that we value or love.

For example, realizing that our life is finite and fragile can make us cherish the moments we spend with our loved ones, or the beauty that surrounds us. In this way, negative feelings can co-occur or alternate with positive emotions, such as joy, gratitude, or wonder, resulting in a bittersweet melancholy.

OTA: It’s a term with a long history, used by Galen, Freud, and others. In what way is their understanding different from yours?

HM: Galen believed that people’s personality and behaviour was determined by an excess (or lack) of four bodily fluids, called "humours": blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Based on this he made an influential distinction between four fundamental personality types: sanguine, phlegmatic, choleric, and melancholic (from melas, ‘dark’, and kholē, ‘bile’). The melancholic condition was believed to be linked to despondency, persistent fears, sleeplessness, and delusions.

Freud – and now we’re skipping almost two millennia – famously thought of ‘melancholia’ as a pathological response to loss. It happens when the recognition of loss is withdrawn from consciousness in such a way that the ego cannot detach from it. Instead, the ego identifies with the lost object and turns the aggression against itself, resulting in a lowering of self-esteem, a loss of the capacity to love, a loss of interest in the outside world.

Freud’s view is certainly distinct from Galen’s, but what both have in common is that melancholia is seen as a fundamentally undesirable and unpleasant state. And that’s where the main difference lies between their theories and my account of melancholy. I am interested in a particular state or experience that is usually valued and even positively cherished. It’s characterized by its bittersweet nature and one may have it in response to art works or to certain poignant circumstances.

For example, a walk in the countryside during autumn, when leaves are falling and the first chill is in the air, can evoke this feeling. Similarly, listening to a song like Judee Sill's ‘The Kiss' can leave one with a powerful sense of bittersweetness. This feeling is something that one can savor, and there doesn’t seem to be anything pathological about it. That’s why I felt the need to develop a new account of melancholy, one that is distinct from Freud and other clinical accounts.

OTA: You reference Emily Brady and Arto Haapala’s essay, “Melancholy as an Aesthetic Emotion" in your paper. Could you briefly tell us about their view?

HM: Yes, Brady and Haapala are one of the few authors to conceive of melancholy as a valuable experience with a distinctive aesthetic character. They put forward two necessary conditions for melancholy. One is that melancholy is always reflective in nature, the other is that it always involves a combination of pleasure and displeasure.

OTA: This is what, according to Brady and Haapala, differentiates melancholy from simply "being sad"?

HM: That’s right. Sadness is a negative emotion, whereas melancholy has negative and positive aspects. And sadness, they argue, is an immediate response to loss, whereas melancholy is more of a delayed or lingering response. It will involve reflection on or contemplation of a person, place or event. They give the example of being in desolate place where you start to ruminate on the past. You feel some pleasure in recollecting good times, but equally some loneliness or feelings of emptiness.

OTA: Your paper makes a few critiques of the account of melancholy presented by Brady and Haapala.

HM: I give a number of reasons in my paper, but one important objection is that their account does not adequately distinguish melancholy from certain other emotional states. For instance, melancholy is supposed to lack the immediacy and brevity of sadness. But is sadness necessarily brief and immediate? I’m not so sure.

Likewise, Brady and Haapala suggest that melancholy is more ‘refined’ than sadness because of its reflective nature. But oftentimes sadness will be equally conducive of a reflective state. So, I don’t think the distinction is as clear cut as they want it to be.

Consider also the way they define melancholy as a complex emotion, with aspects of both pain and pleasure, which draws on a range of feelings such as love, loneliness and longing, all of which are bound with a reflective state of mind. That definition also seems to apply to nostalgia, which I think is distinct from melancholy. It even applies to emotions that are very different from melancholy, such as a brooding jealousy – a state in which painful suspicions of unfaithfulness alternate with gratifying fantasies of retribution.

OTA: What makes nostalgia distinct from melancholy?

HM: It’s quite common to use these terms interchangeably. After all, both are bittersweet emotions, and the realization of transience, which is key to nostalgia, can also bring about melancholy. Still, I think it’s better to keep the two apart. Nostalgia is usually defined as a backward-looking longing where one has positive feelings about the imagined past and negative feelings about the gap between that imagined past and the actual present.

Melancholy, by contrast, is not always or necessarily backward-looking. In fact, melancholy is often triggered by forward-looking deliberations about, say, one’s own mortality or the oblivion that awaits us all. Also, nostalgia typically comes with bitter feelings towards the present. Melancholy does not. Melancholy is often accompanied by an attitude of acceptance and appreciation towards the present.

"Melancholy", an engraving by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione.

OTA: Melancholy is typically perceived as a negative, or at least undesirable, thing. But as the Brady and Haapala essay mentioned, it is "something we even desire from time to time." Why do you think that is? Why is it a state that we sometimes seek out? Is it just because of the pleasurable, nice feeling - or is there something more to it?

HM: There’s more to it, I think. It’s never just the ‘sweet’ aspect of melancholy that we value. We value the bittersweet experience as a whole, and we tend to rank it above many experiences that are unambiguously pleasurable. Why that is becomes less of a mystery if we consider the two components of the account I have proposed. When a person experiences melancholy, they come to grasp an important truth about human existence that is not normally at the front of their minds and that they sometimes even choose to ignore.

Hence, the sense of profundity that seems inherent to melancholy. These existential insights then produce a clearer view of what really matters and prompt a deeper appreciation for someone or something they care about. Hence, the transformative and the aesthetic potential of melancholy. When viewed in this light, it is easier to understand why people seek out and savour such bittersweet moments. Much more than pleasure, it is about insight, appreciation, receptiveness, and even transformation.

OTA: You mention a few other similar concepts in other cultures, notably fago on the South Pacific Island of Ifaluk, saudade in Portuguese, or samvega in Pali. Could you elaborate on those?

HM: Sure, but I should preface this by saying that I have no real expertise in this area. I just thought it was important to underline the historical and cultural specificity of the notion of melancholy. To do so, I referred to some concepts in other cultures that seem to denote similar experiences and that might help to enrich the account I presented.

For instance, on the South Pacific Island of Ifaluk, there is the term ‘fago’, which may be glossed as ‘sad love’. It refers to the love that a person may feel for the less fortunate. ‘Fago’ compels you to care for someone in need but is also haunted by a strong sense that one day you will lose them.

The Portuguese notion of ‘saudade’, that people might know from Fado music, is another example. The Pali word ‘samvega’ I encountered in an interesting article published long ago by A.K. Coomaraswamy. The term is used to denote a poignant realization of the transience of natural beauty but can also refer to certain deeply felt encounters with works of art, when painful themes are offset by the gladdening recollection of the Buddha.

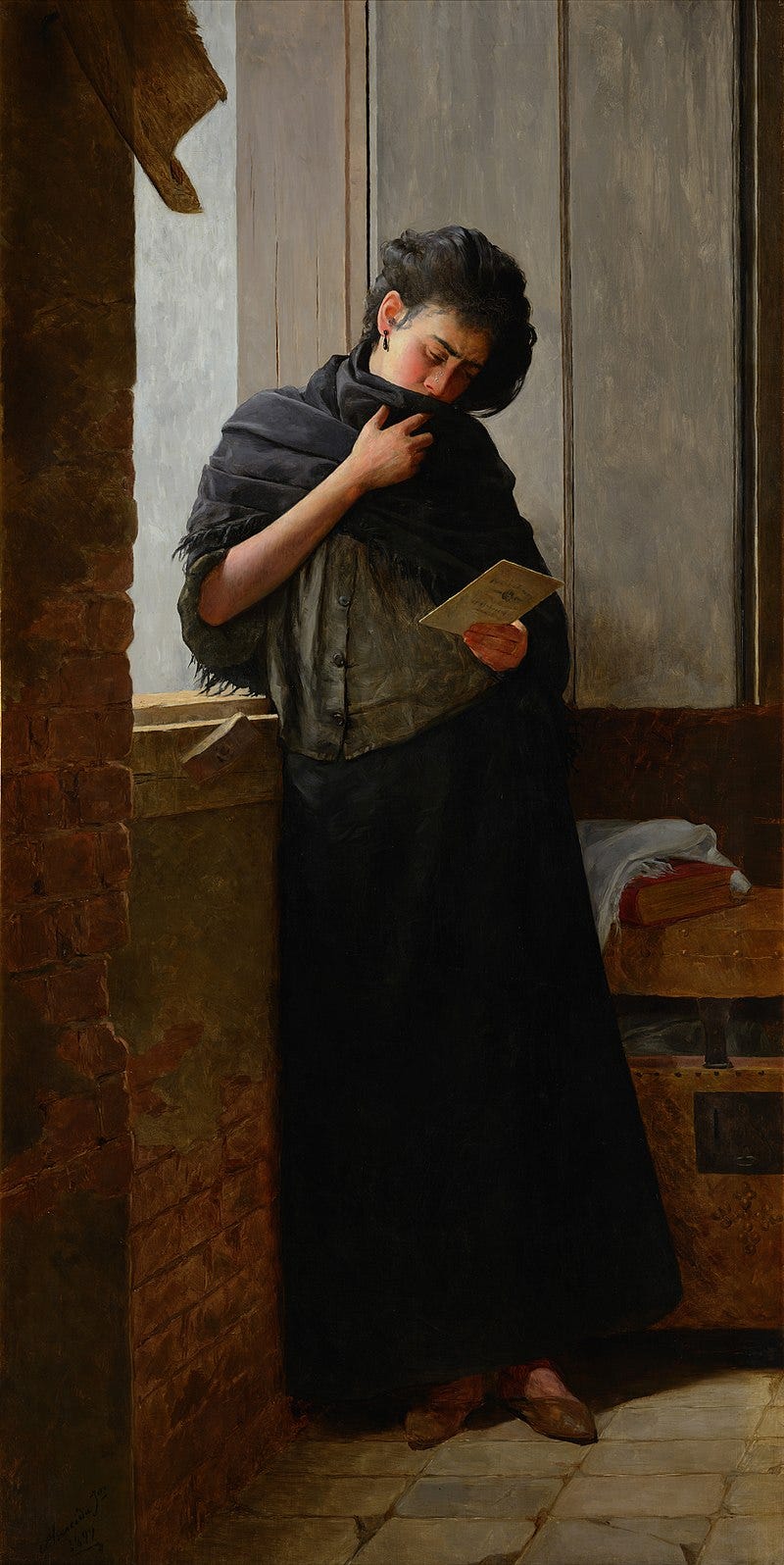

Saudade (1899), by Almeida Júnior

OTA: Chekhov and Tolstoy used melancholy quite often in their works and you return to them throughout the paper. Could you elaborate on that?

HM: This was actually one of the reasons for writing my paper. I have a deep and longstanding admiration for the work of Chekhov and Tolstoy. Tolstoy’s novels in particular have had a tremendous impact on me. But it was only two or three years ago that I asked myself why it is that his work speaks to me so much. The answer, of course, is complicated. But the fact that his work evokes and expresses melancholy in so many ways, and so lucidly, is no doubt one of the reasons why I have been so moved and shaped by his writing.

OTA: I wrote an article on the Gothic a few months ago. While I was reading your paper, it reminded me of Gothic architecture, which does seem to inspire a melancholic mood. Do you think the Gothic has a relationship to the melancholic?

HM: I think my account offers a decent explanation of why some places, more than others, put one in a melancholic frame of mind. As I mention in the paper, sites with a melancholic air are those that easily trigger existential musings on, for instance, the transience of human life or the ultimate insignificance of all our endeavors. The architecture that we often associate with Gothic literature – ruins of castles, old cemeteries – likely belongs to that category. So do Gothic cathedrals, such as the one in Canterbury where I teach. There’s an exquisitely melancholic passage in David Copperfield where Charles Dickens ruminates about the many who have lived and loved and died in the shadows of Canterbury Cathedral.

Early in the morning, I sauntered through the dear old tranquil streets, and again mingled with the shadows of the venerable gateways and churches. The rooks were sailing about the cathedral towers; and the towers themselves, overlooking many a long unaltered mile of the rich country and its pleasant streams, were cutting the bright morning air, as if there were no such thing as change on earth. Yet the bells, when they sounded, told me sorrowfully of change in everything; told me of their own age, and my pretty Dora’s youth; and of the many, never old, who had lived and loved and died, while the reverberations of the bells had hummed through the rusty armour of the Black Prince hanging up within, and, motes upon the deep of Time, had lost themselves in air, as circles do in water.

From “David Copperfield” by Charles Dickens

OTA: I also wrote a piece on the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which covers similar feelings -- especially to your proposed definition of melancholy, which includes "the transience of all things" – a key part of the wabi-sabi ideal. You also mention "mono no aware" in your paper, which is often discussed with wabi-sabi. Do you think there is a very close connection between melancholy and mono no aware?

HM: The short answer is ‘yes’. As you point out in your article, wabi-sabi is an idea in Japanese aesthetics that focuses on impermanence and the inevitable imperfection of human existence. Those are, if you want, important existential truths and so they will be key ingredients of what I call aesthetic melancholy. Similarly, ‘mono no aware’, which is sometimes translated as the ‘pathos of things’, refers to the wistful feeling one has when contemplating the transient beauty of life. Again, I am no expert in cross-cultural aesthetics, but it seems clear to me that there are many interesting points of overlap here that are worth further investigation.

You mention a few films in the paper, including Ikiru and Late Spring. Do you have any thoughts on the film Melancholia? Or recommend any other films, books, or other works of art related to melancholy?

I have many thoughts on the Melancholia, which I consider Lars von Trier’s best film, along with Dogville. But it would probably take us too long to go into detail, all the more because von Trier’s conception of melancholia is much closer to Freud’s than it is to my view on the matter. But I’m happy to give other recommendations for readers who are interested in the particular bittersweet feeling as I have described it.

The film Barry Lyndon, directed by Stanley Kubrick, is soaked in delightful colour and yet also bleak to its core. It never fails to instill me with a deep sense of melancholy. The same goes for Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garret and Billy the Kid or Marco Tullio Giordana’s La Meglio Gioventù.

Some of the photobooks I cherish the most, such as For Brigitte by Titus Simoens and Anonymous Men and Women by Issei Suda, have a distinctive melancholic beauty to them. For people who like dance, I can recommend Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s amazing Laid in Earth (interpreted for screen by Thomas James).

In contemporary visual art there’s the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and, more recently, Ellen Harvey’s The Disappointed Tourist series. Needless to say, music offers a treasure trove of melancholic works. But I’m pretty confident that people can think of good musical examples without my help.

I love reading this🤍 Thank you so much

Awesome interview, I learned about so many new concepts here. Thank you for sharing!