What does Wabi-Sabi really mean?

Explaining an often misunderstood idea in Japanese aesthetics.

Wabi-sabi is one of those concepts that seems to mean just about everything. In the West, it seems to be used to refer to anything that seems “traditional” in Japanese art and architecture. This, as you can probably guess, is not an accurate definition.

But what does wabi-sabi actually mean? In this post, I’ll briefly attempt to define it by looking at the history of the concept. The short version is this: wabi-sabi is an idea in Japanese aesthetics that focuses on impermanence and imperfection.

Before jumping into a longer definition of wabi-sabi, however, there are three things to keep in mind:

The first is that wabi-sabi, like many other terms in Japanese aesthetics, does not have an extremely specific, exclusionary definition. To quote the introduction of Donald Keene's A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics (bold emphasis mine):

In writing about traditional Asian aesthetics, the conventions of a Western discourse—order, logical progression, symmetry—impose upon the subject an aspect that does not belong to it. Among other ideas, Eastern aesthetics suggests that ordered structure contrives, that logical exposition falsifies, and that linear, consecutive argument eventually limits.

As the aesthetician Itoh Teiji has stated regarding the difficulties that Japanese experience in defining aesthetics: “The dilemma we face is that our grasp is intuitive and perceptual rather than rational and logical.” Aesthetic enjoyment recognizes artistic patterns, but such patterns cannot be too rigid or too circumscribed.

Most likely to succeed in defining Japanese aesthetics is a net of associations composed of listings or jottings, connected intuitively, that fills in a background and renders the subject visible. Hence the Japanese uses for juxtaposition, for assembling, for bricolage.

So, one should be careful not to focus too much on the idea that "wabi-sabi is this specific idea and not something else." It is not a formal, structured definition in the way mimesis or representation are.

Instead, the subject of Japanese aesthetics is more like a net, with individual concepts like wabi or sabi overlapping with each other and with other concepts like miyabi, furyu, or yūgen. Also, the influence of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Shinto cannot easily be separated from “purely artistic” topics, just as the influence of Christianity cannot be easily separated from Italian Renaissance art.

The second thing to note about wabi-sabi is that, contrary to many blog posts on the Internet, it is not the "only" aesthetic mentality of contemporary Japan. While a visitor to Japan in 2023 will notice some things influenced by wabi-sabi, he will probably notice kawaii or Western-influenced objects more. Like any other country, Japan has a rich history of competing ideas that have manifested themselves in various ways in modern culture.

Wabi-sabi is generally considered to be more representative of traditional, not contemporary, Japanese art and aesthetics. However, it is still very much an influence on Japanese culture, if a more subtle one.

Finally, the third thing to note is that wabi and sabi are actually different concepts that are often paired together, as Keene suggests, because “…the accidental alliteration of the words suggests a fruitful affinity. And the two are related, to be sure, both in their affinity and in their histories.”

Now let’s look at what wabi and sabi really mean.

Wabi

In one sentence, wabi means an understated beauty, a rustic simplicity, or an austere, noble poverty – but aesthetically, not politically, focused. The word comes from the verb wabu (to fade, dwindle). Its adjectival form wabishi (forsaken, deserted) originally had an unpleasant meaning, but by the Kamakura Period (1185–1333), it began to have a more positive connotation.

D. T. Suzuki, the well-known 20th-century Zen scholar and author, described wabi as:

…an active aesthetical appreciation of poverty… [wabi means] to be satisfied with a little hut, like the log cabin of Thoreau . . . with a dish of vegetables picked in the neighboring fields, and perhaps listening to the pattering of a gentle spring rainfall.

The pursuer of wabi isn’t interested in fame, wealth, power, abundance, opulence, or popularity. Instead, he seeks an elegant simplicity, typically in natural surroundings. He doesn’t create objects with expensive, rare metals, instead using simpler, organic materials. Wabi isn’t about asceticism or glorifying poverty, however. The idea is that less is more sophisticated, not that objects themselves are to be despised.

In art and architecture, wabi is best exemplified by the tea house, which we will discuss a bit later. Other wabi-influenced items are the dry rock garden and pottery, often with kintsugi golden repair joinery.

In the West, we don’t have the same historical concept of wabi, but the philosophy of Thoreau’s Walden or later Simple Living Movements might be comparable examples.

Wabi would also play a key role in the Tea Ceremony, but more on that later. First, let’s look at sabi.

Sabi

In one sentence, sabi means having a rustic patina and showing the marks of age – all with a hint of solitude. Originally, the word had the negative meaning of “desolate.” But over time, it was used to describe something that has aged well and acquired a beautiful patina.

The word itself has many sources:

sabu, a verb meaning “to wane”

susabi, a noun which can mean “desolation”

sabiteru, “to become rusty,” and thus “to become old”

sabishi, an adjective which means “lonely”

another word that is also pronounced "sabi" means “rust”

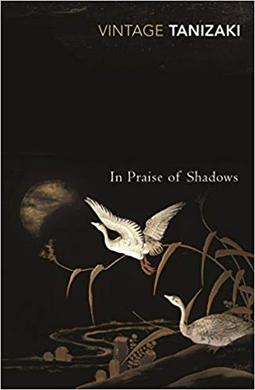

In his essay In Praise of Shadows, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki discusses the appeal of sabi in traditional Japanese culture:

We [Japanese] do not dislike everything that shines, but we do prefer a pensive lustre to a shallow brilliance, a murky light that, whether in a stone or an artifact, bespeaks a sheen of antiquity…

We love things that bear the marks of grime, soot, and weather, and we love the colors and the sheen that call to mind the past that made them.

In Praise of Shadows

There is also a hint of solitude, loneliness, and melancholy in sabi. Basho (1644-1694), the most famous haiku poet, was a key figure in modernizing the “positive” nature of sabi. In his haikus, he used sabi to emphasize the tranquility or peace that results from loneliness.

Solitary now —

Standing amidst the blossoms

Is a cypress tree.

Basho

A Western example of sabi might be the continued appeal of Urbex (Urban Exploration) photos, which depict the beauty of abandoned structures. There is also a Japanese equivalent of Urbex called Haikyo. The Statue of Liberty also has a nice sabi patina to it, as the original copper color has oxidized into its current grayish-green color.

An episode from history perhaps best explains sabi. In 1950, a Buddhist acolyte, disturbed by the immense beauty of the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto, lit it on fire, burning it to the ground. An exact replica was put up on the same site five years later. In the 1980s, thanks to Japan’s thriving economy, the building was covered entirely in gold leaf – as the original creator had intended.

Upon seeing the new structure, many residents of Kyoto complained that it would take many years for the building to re-acquire the sabi that had made the old version so beautiful.

But what about the Tea Ceremony?

The Tea Ceremony

If you read about the history of wabi-sabi, you’ll probably see the Japanese Tea Ceremony mentioned as exemplary of the concept. This is essentially true; although there are hints of wabi and sabi in earlier centuries (especially in poetry), it’s ultimately the Tea Ceremony (known as sadō/chadō 'The Way of Tea') that tied wabi and sabi to each other and more broadly to Zen Buddhism.

Tea itself first came to Japan in the 800s, brought by a Buddhist monk returning from China. By the 1200s, tea had become a status symbol among the upper classes. A few centuries later, inspired by his studies of Zen Buddhism, Murata Jukō introduced many of the aesthetic and philosophical ideas of the tea ceremony. These included the use of rustic and imperfect Japanese tea utensils (as opposed to only using the perfect, intricate Chinese designs), the importance of Buddhist ethical concepts, and the preference for smaller teahouses, typically only 4.5 tatami mats (7.4 m2; 80 sq. ft.)

A few generations later, Sen no Rikyū further developed and codified these ideas (which were very influenced by wabi and sabi) while working as the tea master to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a feudal lord and de-facto ruler of Japan.

To summarize a very long story, the Tea Ceremony became intimately linked with Japanese politics and later developed into various schools that exist to this day. Many of these continued the wabi-sabi ideals of Rikyū, while others went in different directions.