Plastic palm trees and inflatable pineapples

An Interview with Max Ryynänen on the Tropical Kitsch

Max Ryynänen is Principal University Lecturer at Aalto University, Finland. In the interview below, we discuss the concept of “tropical kitsch” and its relationship to tourism, consumerism, and kitsch as a whole. The full paper, Making Sense of Tropical Kitsch (co-authored with Anna-Sofia Sysser) is online at Contemporary Aesthetics.

On the Arts: Kitsch is a word familiar to most people, but it can be difficult to define and has a variety of meanings. How do you define it?

Max Ryynänen: I think the most important thing to note is that kitsch is a concept which comes from a certain geographical area and a certain time period. “Kitsch” won an international race against many other concepts in the late 19th Century.

Russian had and still has Poshlost, which could be used for example about a sneaky politician as much as about a vase which represents bad taste. Spanish had and still has cursi, which means corny and sentimental. There were many concepts around in the 19th Century, like French Camelot and Shlock (probably Yiddish).

There was a need, in the mid-19th Century to find a concept for the growing amount of sentimental, a bit sugared, sleazy, mass produced or stereotypical (fake artistic) culture. Middle class taste was changing, and so were the means of mass production too. And, also, the art system had just appeared on the scene – seeking for hierarchically lower ‘enemies’. Kitsch was good for that. One could say, “this is real art”, and that is just “kitsch”.

As a Southern German concept – originally from Munich, 1860s – it builds on Southern German 19th Century metaphysics, and thinking typical for that period. “Kitsch” has no originality nor depth, and it is stereotypical, often pretentious. This is how the original meaning has it. One can still feel this underlying base in today’s concept. If it would have been created in Brazil or Japan, it would have a different base.

Today, the Western cultural elite is no longer against everyday culture nor does it have a problem with sentimental culture to the extent it used to have. So, kitsch has become a more positive concept. Also, we apply it freely to many different things and with different reasons. Some colors, like pink, evoke the use of the word easier than others. Porcelain is easier conceived of as kitsch than bronze.

This all leads to the craft and mass-production history of early modern life. Now we of course discuss even Taiwanese cat puppets as kitsch, and for sure, Western production has affected them too, but in the end, there are many levels and ways of applying the concept today.

Anyway, although “kitsch” can mean many different things, it has a root, which it seems to not get rid of, at least not totally. For anyone into the history of the concept, Matei Calinescu’s essay on kitsch in his book Five Faces of Modernity (1986) is a great start. For more contemporary changes in the concept, I sadly cannot really recommend anything othern than the introduction I wrote with Paco Barragán for The Changing Meanings of Kitsch (Palgrave, 2023) – which talks about the issue globally too.

OTA: How would you define tropical kitsch?

MR: The interesting thing in countries like Finland, where I live, is that our culture is not very colorful. Often when it is, in spas or at the beach in the summer, it is labeled ‘tropical’. The concept of the tropical seems to be anchored to pineapples, flamingos, banal soft objects, and so on – and often only there do we, who live up north, find pure bright colors.

The tropical as a concept leads to the geographical south, but it has of course also roots in European colonialism (although e.g., here in Finland, we did not have southern colonies, so the concept arrived to a more naïve context).

As a kitsch scholar I worked with Anna-Sofia Sysser on this topic. She is an artist and a scholar who has worked on the issue of the tropical, both in art and through writing. We wanted to raise awareness of this weird cultural issue. Banal objects like inflatable bananas and plastic palm trees are a part of this phenomenon, which has not yet fostered much discussion.

OTA: The concept of the tropic as aesthetic has a long history, but as you note, it wasn't present in the Renaissance or the Enlightenment. Could you tell us a brief history of the tropical idea in Western culture?

MR: The history of the concept is tricky, and goes back to both geography and colonialism, like I said. It has some tricky political roots, but it has also been just used about certain areas – where e.g., pineapples grow. One could go deep into those problems from a post-colonial perspective.

What is interesting, though, e.g., up north, like here where I live, it is often used in a very naïve, curious way. We have a lot of snow, and people are often also just curious about the south. Many wish they’d live somewhere where they could go to the beach every day. The concept has arrived from dominant Western countries like England and France, but here the simplifying, positive way it is used, is a bit of a utopian one. I suppose this could be the case in many countries in the Global North without a colonial history in the south. It is a naïve aesthetic utopia, which still, of course, bears traces of the colonial adventures of colonialist Europe (Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, etc.).

OTA: As you note, many tropical kitsch items function as icons representing "warm weather" or "the beach" and don't actually refer to a specific place or object – indeed, they are not actual representations of the real countries in the tropics, which often are savannas or mountains, not islands with beaches.

MR: Yes, they are a bit like banal visual tags. The inflatable banana which my daughter sometimes likes to swim with and the plastic palm tree in the spa where my university unit organizes a recreation day are simple icons.

On a basic level they tell us about warmth and certain tastes (fruit, e.g.), but of course, during that kind of a recreation day we laugh about it, and see weird connections to colonial imagery, tourism advertisement, and many other cultural issues. This affects of course the South too.

In Southern India people sell stuff as tropical – with, weirdly (this is something Anna-Sofia works on), the same imagery, and the same aesthetic. Interestingly, and nicely, this phenomenon, though, makes possible the use of bright colors. We can have fun with yellow color for example, which is otherwise not much present in many cultures of the North.

OTA: Do you think that Miami Vice, Scarface, and other 80s films had a role in spreading this aesthetic to a larger audience? Miami and Florida especially seem to promote this "tropical but modern location" in a lot of movies and TV shows.

MR: Films have for sure had an impact on spreading this visual imagery. I think Florida is a topos, which has affected the whole US. Miami Vice as much as John Waters’ Pink Flamingos are about the visual imagery of certain tropical areas.

But the imagery was distributed also by 19th-Century kitsch objects, small and cute things you could bring home from the tropics or buy in big cities like in London. Celeste Olalquiaga’s The Artificial Kingdom (1998) is a great book about this. One can trace the way the tropical has affected the production and consumption of cheesy, small, cute objects easily at least to the early 19th Century.

OTA: Other than Florida-related American media, who or what else would you consider to be influential on popularizing tropical aesthetic in modern times?

MR: Well, it is quite natural that products meant to be used on the beach don’t feature images of polar bears or reindeer... I suppose anything related to the tropical south and leisure easily goes for symbols everyone knows. Some are also easier, like pineapples and bananas. I like mangos more, but visually they are harder to get.

There are also, of course, conventions. Someone went for the pineapple more than bananas, and now that concept is more in the DNA of the whole culture of tropical kitsch. There might be no other reason for it.

Getting back to other influences, the French, also, have for sure, created their own “tropical south” in literature and painting already long time ago. Think of Paul Gauguin, and his kind of sleazy adventures in Tahiti – which could, anyway, (I think this side of it is a nice, positive one) spread bright colors into Western visual art.

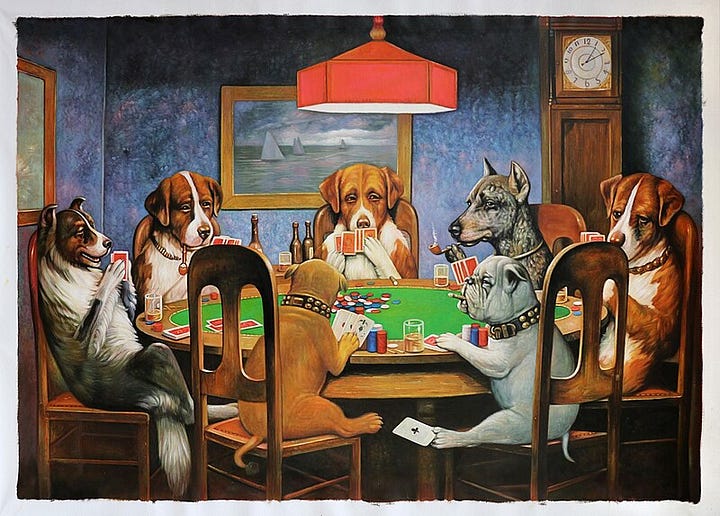

OTA: Tropical kitsch seems to get a less hostile reaction than other types of kitsch. For example, a piña colada in a decorated cup is just a drink you get at the bar, while no “serious” person would ever hang a painting of dogs playing cards in their house. I’m wondering if it's because other types of kitsch are more sentimental, whereas tropical kitsch is more escapist and touristic. Why do you think that it has less of a negative reaction?

MR: Well, at least this is true: in the Global North we feel that we need more warmth (we will now get slowly, in a sad way, as we know from climate change, but this is not what we dreamt about) and we need bright colors too (which our cultures often don’t really accept in the everyday). We need tropical kitsch around us.

The dog is just a motive for an image. We might want to cuddle dogs, but they don’t relate to this big thing that we are lacking, and which we have segregated into spas, juice cans, and so on.

Also, it could just be about conventions. There is a convention to have images of mountains on the wall, but not gravel pits – although I think most gravel pits look actually really interesting. The same way, you can have pasta or piña colada on the wall, but not kiwis and dal (to take up two tropical food products) – without someone asking what’s that about. Maybe if we’d have a Tom Cruise movie where they eat kiwis and make love on the beach, and then eat dal and discuss romantically, this might become a thing.

OTA: It also seems like many southern European vacation destinations are branding themselves in a somewhat tropical kitschy way. I'm thinking here of Split, Croatia, which I've been to many times. The main waterfront avenue is lined with palm trees. I looked into this a bit and apparently the first palm trees were planted in Split about a hundred years ago when tourism started picking up. This is fairly recent for the city, which was founded in the ruins of a Roman palace and thus quite old.

MR: Yes, this is interesting, actually, what you say. I think in many places where there are tourists in the south, they build also the imagery of the tropical through real things, like real palm trees. But it applies to all tourist destinations in the end, that they are already built for tourists. Venice built bridges for tourists. Originally you could not walk there, really. In Helsinki, we don’t spend any time in houses built with ice. We like warm houses, for a reason... But tourists have an ice bar and even a hotel made out of ice. We have never been inside of those.

OTA: What happens when elements of the tropical aesthetic are adopted by northern countries in their "serious" aesthetic? For example, when buildings are painted in bright colors and more “southern” greenery (like palm trees) are added to an urban space. Does this lessen the power of tropical kitsch as a symbol of escapism to a brighter, sunnier place? Or is it just a reminder of the real one?

I have not noticed much competition in this sense. It seems that tropical kitsch is still the thing in most places in the North. But of course, colorful buildings might become a hit any day – e.g., after the success of the Barbie movie? If our everyday becomes bright enough, though, I think it could destroy some of the pleasures now hidden in the use of tropical kitsch.

OTA: Similarly, do you think climate change might impact the tropical kitsch, especially in Europe? This summer has seen record temperatures and the last few winters seemed very mild. If the element of leaving northern climates to "escape" to warmer southern ones becomes less necessary, will the appeal of the tropical kitsch fade?

Well, this is hard to say, but for sure our idea of the warm south is changing... It is still countries like Italy which we think about, not the tropical ones (which might get even longer rainy seasons). How much will climate change affect the aesthetic utopia of tropical kitsch?

Often utopias survive, as they are anyway not about the real world. Look what happened with Marxism: the socialist system was in many ways worse than real capitalism, but people kept dreaming in the West. Maybe tropical kitsch becomes, in the end, with time, nostalgic? Culture changes in ways which are hard to predict!