Modern Culture is Too Escapist, Part 1: Isolated vs. Integrated Arts

Too much creative energy is focused on escaping the world, not on enhancing it.

This is the first post in a three-part series. In this first post, I argue that the arts today are too escapist and why that’s a bad thing. In the forthcoming Parts 2 and 3, I will explain how this happened – and how we can try to fix it.

It seems to me that we can divide the arts into two basic categories:

Art that is experienced in a separated or isolated state. In this category, we can include art galleries, films in theaters, theatrical plays, reading a book alone, most video games, watching videos on your phone, listening to music via headphones, and so on. We can call these isolated arts, as they are separated from everyday life and are often (but not always) escapist in nature.

Art that is integrated with the world and enhances life as it is being lived. In this category, we can include architecture, interior design, landscape architecture, gardening, street musicians, public transportation, urban design, and everyday objects like furniture or dinner utensils. We can call these integrated arts, as their artistic qualities are experienced as a part of other activities in life.

Of course, these aren’t strict definitions and the boundaries between the two categories are quite blurry. In general, however, I think it’s a useful distinction. Why is it useful?

Because at the moment, it seems that the “creative energy of civilization” is too focused on the isolated arts – and not enough on the integrated arts. In other words, more creative energy is put toward helping us escape from the real world, rather than enhancing it.

It feels like there is something fundamentally wrong about this situation. Wouldn’t the world be a more beautiful place if more of society’s aesthetic energy was put toward the real world, rather than imaginary ones? Instead of aestheticizing the lives of fictional characters in a Netflix series, aestheticizing our own lives?

Where Does the Money, Time, and Energy Go?

Consider how many resources are put toward a big-budget film or video game, both by its creators and by its consumers. Films routinely cost hundreds of millions of dollars, with video games not far behind. A “low budget” movie is one made for a few million dollars.

From the consumer side, billions of people discuss and debate films, books, and video games, develop expert-like knowledge of their intricate plot details, and dedicate hours of their lives toward experiencing them, all entirely unpaid and without any coercion.

Now compare that to how little money, energy, and time is spent on the aesthetics of the typical housing development, city park, or piece of middle-class consumer furniture. The average new office or apartment building looks basically the same as any other, inside and out, whether you’re in Ohio, Poland, or India.

More tellingly, there is virtually zero cultural debate or interest in most integrated arts when compared to popular TV shows, films, or video games. Imagine the general public caring about the aesthetics of park design or the architecture of subway stations as much as the Barbie movie or the last season of Succession. It seems absurd, yet people in the past did care about such things passionately.

While the hunger for new video games, television series, and other escapist media seems insatiable, we seem to have quietly accepted that the actual physical spaces we live and work in everyday will never change from a “basic box” model. The city of the future we’re building isn’t a sci-fi metropolis filled with flying cars and architecturally innovative skyscrapers; it’s an endless row of glass box buildings with an LCD screen – eventually replaced by a pair of VR goggles – for every resident.

Locked Away

Another consequence of the focus on isolated arts is that it results in a large portion of artistic works remaining behind closed doors: in private collections of billionaires, dormant and zombie-like in freeport zones, or simply in the storage basements of museums, which only display a small percentage of all the works they own.

While you could blame this situation on wealthy collectors and limited museum budgets, I think the issue is actually much deeper and related to this focus on isolated arts.

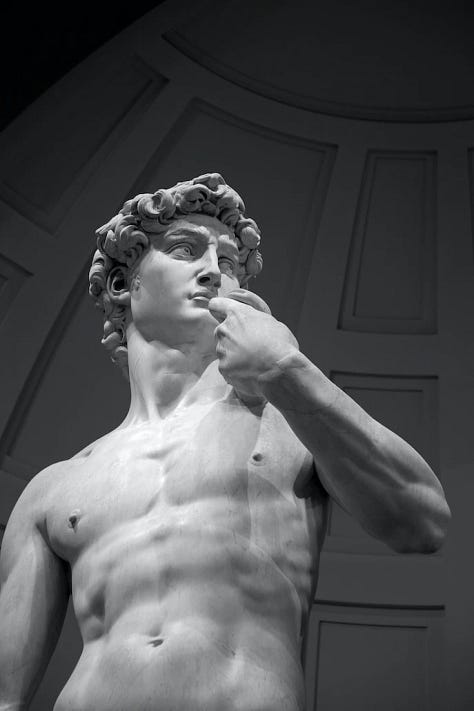

The Italian Renaissance provides a good counter-example of an alternative approach. While there were certainly plenty of private works created by artists during the Renaissance, there was more of a balance between isolation and integration. A significant portion of artistic output was in the public sphere: murals and sculptures were put in churches and town squares, and the design of civic buildings was the subject of intense public debate.

Today, if a wealthy benefactor wanted to emulate a Renaissance patron and fund an architect or artist to create a new town square or city park, it’s unclear how he or she would even go about doing so. There don’t appear to be any financial instruments specifically designed for rewarding investors that fund integrated artworks. The design of the public space would almost certainly be watered down and subject to various governmental councils and community groups. Hostile attitudes toward the wealthy would probably result in the park being vandalized, if it were actually built.

Consequently, it is much easier and more creatively rewarding to instead spend a few million on a rare painting or backing a film project. Put simply, there are very little incentives for the wealthy to fund integrated arts.

Part 2: How We Got Here

How did this focus on isolated arts happen? It is a huge topic, involving technology corporations, arts education, individualism, consumer agency, private property, and even the concept of capital-A Art itself.

In the next post in this series, I’ll explore some of these reasons. In the third post, I’ll suggest some potential solutions.