Istanbul's Blue Tile Paradise

The Hidden Mosque of Rüstem Pasha

Istanbul has a lot of mosques. At last count, nearly 3,000.

When tourists visit the city, they tend to focus on the famous names: the Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque, the Süleymaniye Mosque, or the impressively modern Çamlica Mosque. During a recent trip to Istanbul, however, a lesser-known mosque turned out to be my favorite.

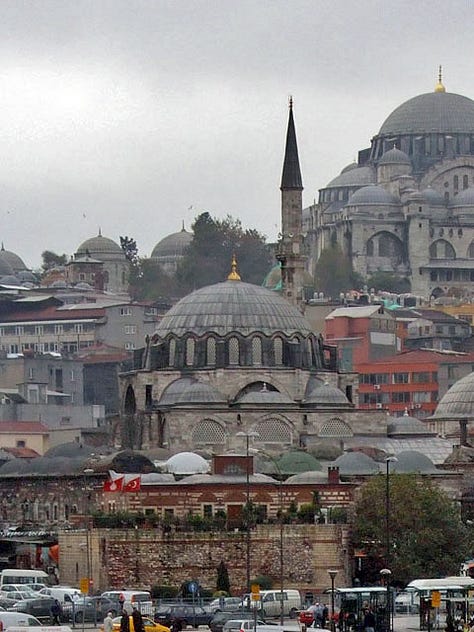

Crouching in the shadows of the much larger Süleymaniye Mosque, the Rüstem Pasha Mosque is like a cave filled with hidden treasure. Built by the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan for the extremely influential – and somewhat controversial – Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha, the mosque is unique in a number of ways.

Unlike the better-known mosques in Istanbul, it isn’t flanked by acres of fountains, flowers, and gardens. Nor does it have grand views of the Bosphorus or of the city itself.

Instead, it’s built on top of a shopping arcade at the edge of a street market. The entrance, a pair of small doorways nestled between a kebab stand and a public restroom, is easy to miss. If you didn’t know it was there, you’d probably never find it.

Through the doorways and up the narrow staircase, you arrive in the mosque’s courtyard. The sensation is that you’ve been transported to an urban oasis. Istanbul’s car traffic, notoriously busy and loud, is only about 100 feet away. The shoulder-to-shoulder crowds of the bazaar are even closer. And yet the sahn, or entrance courtyard, is quiet and mostly empty.

What makes the mosque truly special, however, isn’t simply that it’s hidden. It is the balance between its understated view from the street and an extravagant, richly adorned interior, which is covered in thousands of colorful İznik tiles.

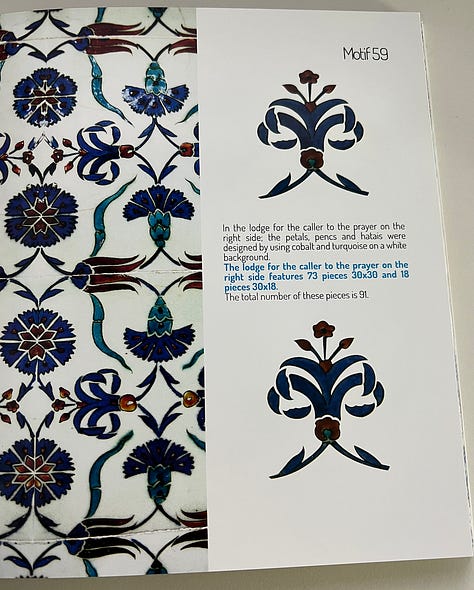

İznik tiles, as the name suggests, come from a town called İznik in western Turkey. Predominately white and blue, the tiles have images of flowers and Arabic sentences from the Qur'an and from hadith, which are records of Muhammad’s life.

Iznik pottery and tiles were used extensively by the Ottomans, especially in religious and political architecture like the Topkapı Palace, the center of government from the 1460s to 1856.

The Rüstem Pasha Mosque is a prime example, with over 2,300 tiles containing 80 different patterns, each with its own specific purpose. To learn more about them, I bought a small book from the mosque’s caretaker, which exhaustively details the variety of motifs used and their symbolic meaning:

While the Rüstem Pasha Mosque lacks the gravitas and sheer scale of the Hagia Sofia or the Süleymaniye Mosque, its human scale and hidden nature lends it a certain magic that is missing in the more monumental structures.