How to Write a Proper Haiku

A Starter's Guide to the Deceptively Simple Poetic Form

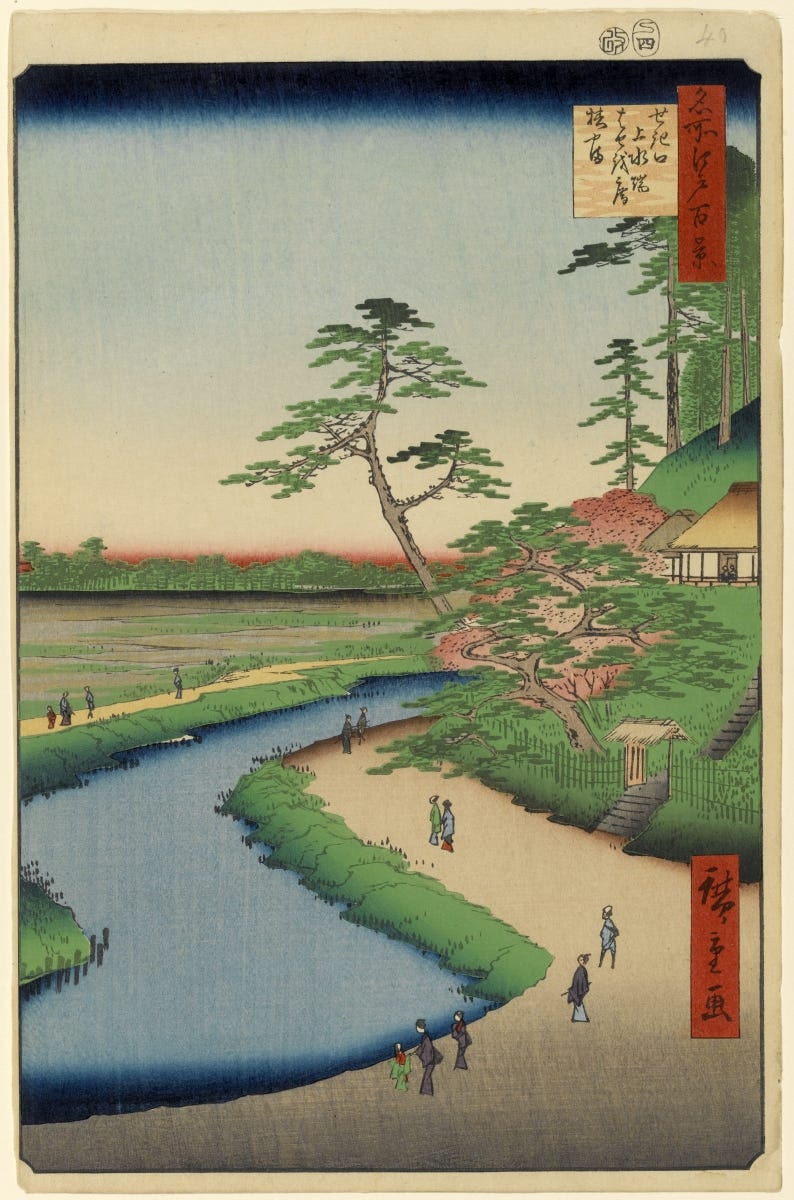

Bashō's Hermitage from Hiroshige's One Hundred Famous Views of Edo

When it comes to poetry, haiku seems to be more popular than almost any other form.

Partly, I think, because of its visual flavor, which can almost be described as painterly or cinematic; and partly because of haiku’s short-but-strict set of rules. As the old rule goes, constraints breed creativity.

So, you want to write a haiku? Here is a brief guide to getting started.

First Understand the Form

What is a haiku, exactly? It depends on whom you’re asking – and how authentic you want to be.

When used in English, the label of “haiku” is a fairly broad one and essentially includes everything that has been inspired by the traditional Japanese form, even if it doesn’t quite follow the same strict set of rules.

This is why you’ll often see books like Jack Kerouac’s Book of Haikus – nearly all of which don’t follow the strict definition of a traditional Japanese haiku.

In English, the most basic type of haiku is simple: a three line poem, like this:

The sound of silence

is all the instruction

You'll get

Jack Kerouac

If you’re entirely new to writing poetry, I recommend beginning with this simple form. While it isn’t exactly “authentic,” it’s much easier as a starting point and it gets you into the mindset of writing haiku. You can always add more rules later.

5-7-5

More typically, however, a haiku in English follows an additional rule: that syllables must follow a 5-7-5 pattern. This means that the first line should have 5 syllables, the second line 7 syllables, and the third line 5 syllables again. If you struggle with determining how many syllables a poem has, this neat little tool can help.

Here is an English haiku that follows the 5-7-5 pattern:

Whitecaps on the bay:

A broken signboard banging

In the April wind.

Richard Wright

Looking at the Kerouac haiku again, we can see that it doesn’t follow the 5-7-5 pattern:

The sound of silence (5)

is all the instruction (6)

You'll get (2)

Does that make it not a haiku? It depends. If we’re aiming to follow the strict 5-7-5 rule, then it clearly doesn’t. But…it’s not quite that simple.

Why? For starters, because syllables aren’t a concept in the Japanese language, which uses something called on instead. On are counted differently than syllables in English…which makes the 5-7-5 rule a little suspect.

On

The words in traditional Japanese haiku don’t follow a 5-7-5 syllable pattern, but instead (usually, but not always) follow a 5-7-5 on pattern. So that’s where the 5-7-5 format originated.

But what is an on?

I won’t delve into Japanese grammar too much, but in short, it basically works like this:

a short syllable counts as one on

an elongated vowel counts as two on

a double consonant counts as two on

an “n” at the end of a syllable adds an additional on

The word haibun (俳文) – a type of literary form that combines haiku with prose – is a useful example to illustrate how this works. In English, this word has two syllables: hai-bun.

In Japanese, however, it has four: ha-i-bu-n, as ai is an elongated vowel (giving it two on) and the word ends with an “n” (adding one on).

As a consequence, Japanese haiku tend to be shorter than English haiku – which throws into question the validity of the 5-7-5 rule when writing haiku in English.

This is easy to observe when comparing the original Japanese words with their English translations. Below, we have perhaps the single most famous Japanese haiku, by the poet Bashō. Note that in Japanese, haiku are traditionally printed in a single line.

古池や蛙飛び込む水の音

ふるいけやかわずとびこむみずのおと

furu ike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

Divided into on, we can see how it follows the 5-7-5 pattern:

fu-ru-i-ke ya (5)

ka-wa-zu to-bi-ko-mu (7)

mi-zu-no-o-to (5)

But if we look at one English translation – of which there are many – it doesn’t conform to the 5-7-5 syllable pattern:

an ancient pond– (4)

a frog jumps in (4)

water’s sound! (2)

Translated by D.T. Suzuki

Subsequently, some English-language haiku poets disregard the 5-7-5 rule and aim to make their haiku shorter, in an attempt to match the original Japanese form. Others consider Japanese on to be the equivalent of English syllables, and thus insist on the 5-7-5 form. The history of haiku in non-Japanese languages is thus a rather diverse one, without a single “correct” approach.

Poet Bashō and Moon Festival (1891) by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Another somewhat novel approach is to focus on the rhythm of the poem and the stress placed on words, rather than the strict number of syllables or on. This paper and this video explain it in far greater detail than I can get into here. For those seeking to truly translate the traditional Japanese “fixed form” (teikei, 定型) into English, this seems like a promising route.

Kigo and Kireji

Now you (hopefully) understand more about the form of a haiku. But what about the content? Traditionally, in Japan, there are two key elements that most haiku contain:

kigo, which is a word symbolizing or referencing the season or time of year. The kigo should come from a designated list of seasonal words and “set the mood” for the poem.

Many of these words can be difficult to spot without a deep knowledge of Japanese culture. For example, in the Bashō poem above, frog is a symbol of the Spring season.kireji, or “cutting word”, which serves as an abrupt turning point or change of subject from one part of the poem to the next. The kireji almost always appears at the end of one of the lines. Because there is no direct equivalent to kireji (cutting words) in English, they are often marked with a dash or ellipsis in translation.

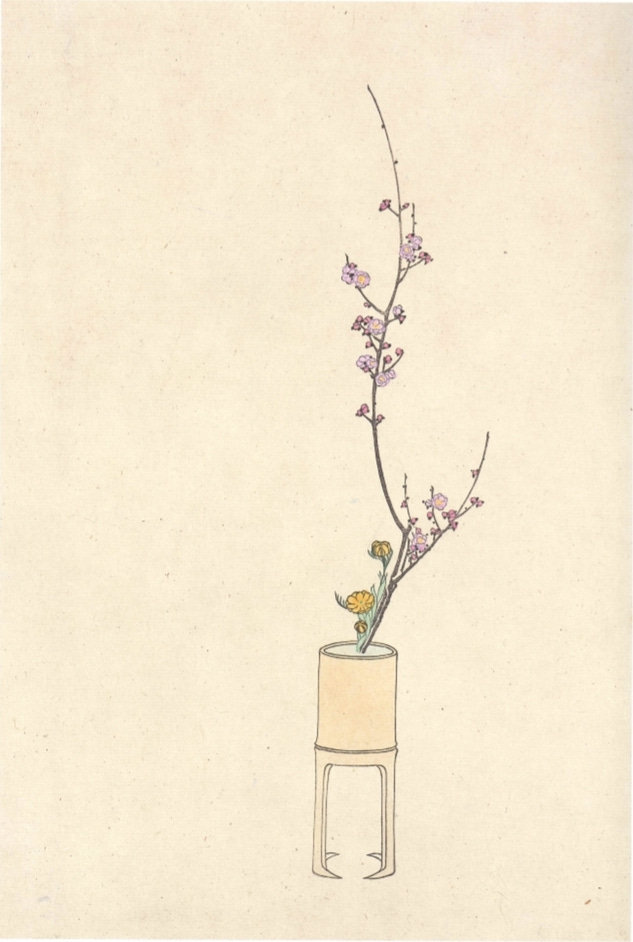

Interestingly, this concept of a “cut” is not unique to haiku poetry and has a long and influential role in Japanese aesthetics, particularly on ikebana flower art, Nō theatre, film cuts, and Zen rock gardens. Ultimately, the concept can be traced back to Buddhist notions of impermanence.

Ikebana, the Japanese art form of flower arrangement. According to Nishitani Keiji, a 20th century Japanese philosopher, cutting a flower from its roots reveals its “true nature” as an impermanent object in an impermanent world – a key concept in Zen Buddhism.

Thankfully, these two concepts are a bit easier to translate into English. To include a kigo equivalent, try to make your haiku about nature. Indeed, most of the best-known historical haiku are about natural subjects.

Seeing as it is autumn in the Northern Hemisphere, this list of autumn-related haiku is a good place to look for inspiration.

The kireji is a little trickier. The easiest way to think about it, in my opinion, is to imagine a film scene where the director quickly cuts from one location or subject to another, apparently unrelated one. Or, when a film cuts from one angle to an entirely different angle, bringing about a different view on the subject.

The main objective is not to merely continue the same line of thought from line one to line three, but to introduce a new perspective or subject matter that nonetheless still relates to the overall topic.

The poem by Bashō below illustrates this well:

Final Notes

As I’ve hopefully conveyed, haiku is both simple and extremely complex at the same time.

If you’re beginning to write haiku, you may wonder, “Do I need to include a kigo and kireji? Does my poem need to follow a 5-7-5 syllable pattern? If I don’t do these things, is my haiku improper or wrong?”

My recommendation? Don’t stress too much about it, at least at first. What makes haiku aesthetically intriguing to me is its short length, adherence to some form of creative restriction, and cinematic quality – and not an over-obsession with following difficult-to-translate rules. Even Bashō and other great haiku masters didn’t always follow them.

Just start with a simple three line poem…and see what happens. You can always introduce additional creative restrictions later.

As a final note: if you’re looking for some haiku inspiration, check out this Instagram account. Its author, Takahiro Dunn, posts short video clips of his life in Japan – a haiku poem with each one.

Excellent. Thank you.